Using Equations

Introduction

ODEs (Ordinary Differential Equations) are often used in ecology or in epidemiology to describe the macroscopic evolution over time of a population. Generally, the whole population is split into several compartments. The state of the population is described by the number of individuals in each compartment. Each equation of the ODE system describes the evolution of the number of individual in a compartment. In such an approach individuals are not taken into account individually, with own features and behaviors. On the contrary, they are aggregated in a compartment and reduced to a number.

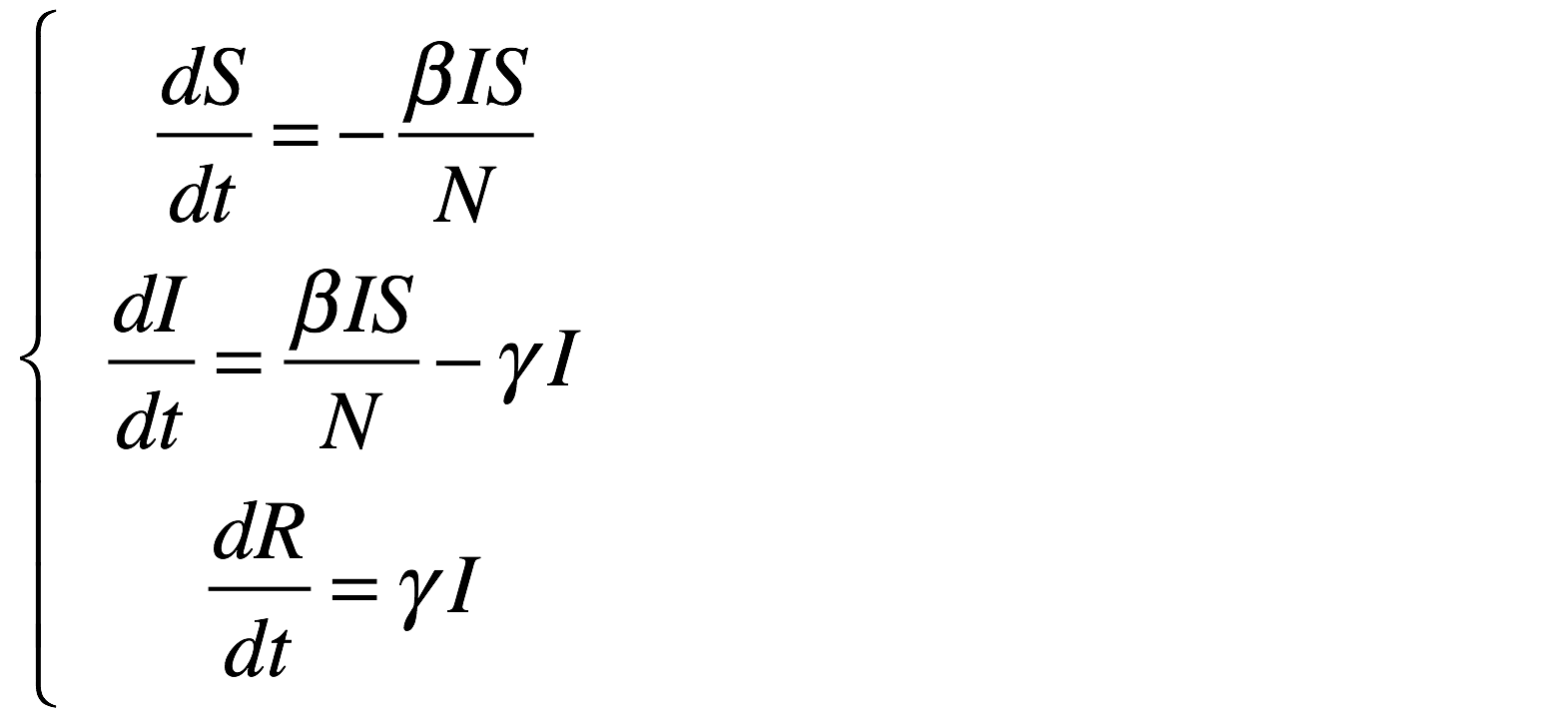

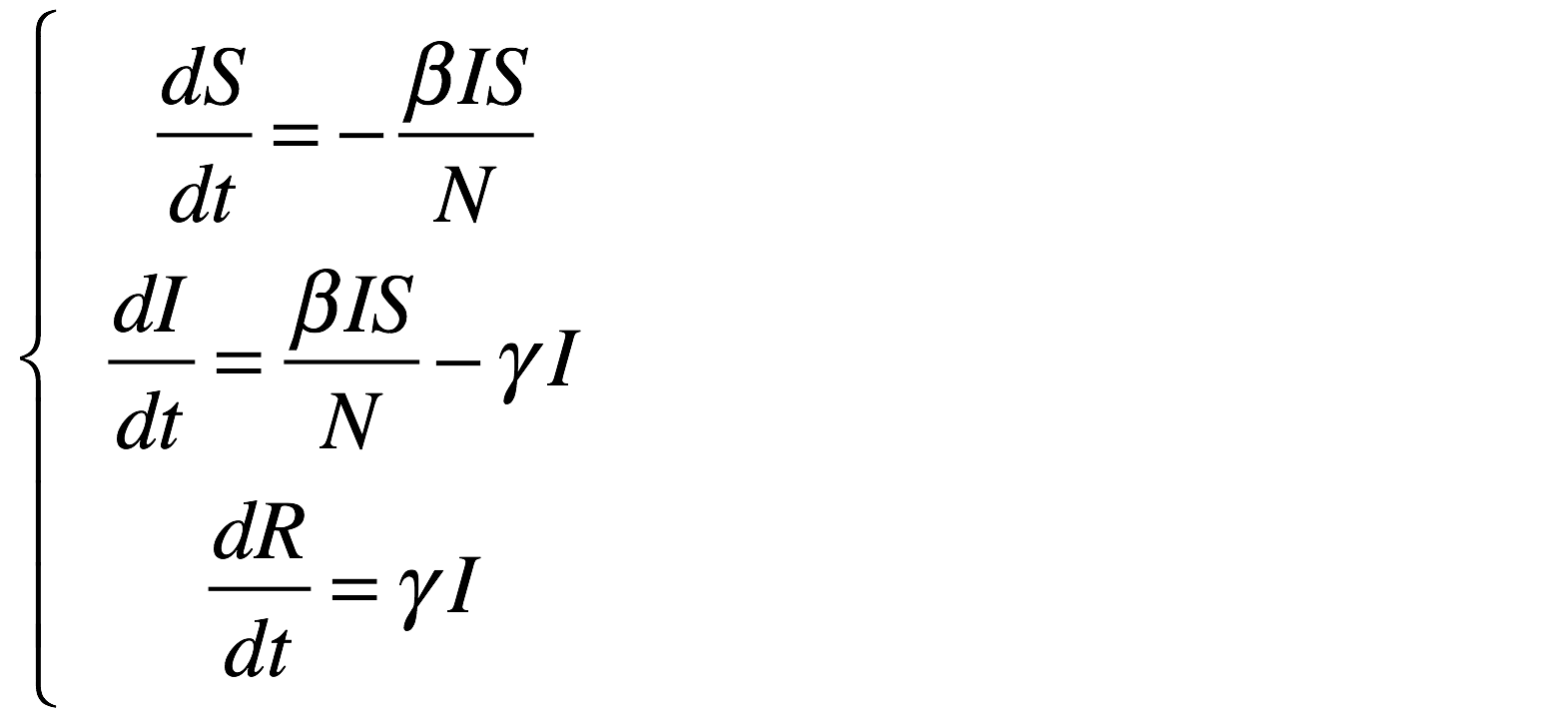

A classical example is the SIR epidemic model representing the spreading of a disease in a population. The population is split into 3 compartments: S (Susceptible), I (Infected), R (Recovered). (see below for the equation)

In general, the ODE systems cannot be analytically solved, i.e. it is not possible to find the equation describing the evolution of the number of S, I or R. But these systems can be numerically integrated to get the evolution. A numerical integration computes step after step the value of S, I and R. Several integration methods exist (e.g. Euler, Runge-Kutta...), each of them being a compromise between accuracy and computation time. The length of the integration step has also a huge impact on precision. These models are deterministic.

This approach makes a lot of strong hypotheses. The model does not take into account space. The population is considered as infinite and homogeneously mixed so that any agent can interact with any other one.

Example of a SIR model

In the SIR model, the population is split into 3 compartments: S (Susceptible), I (Infected), R (Recovered). This can be represented by the following Forrester diagram: boxes represent stocks (i.e. compartments) and arrows are flows. Arrows hold the rate of a compartment population flowing to another compartment.

The corresponding ODE system contains one equation per stock. For example, the I compartment evolution is influenced by an inner (so positive) flow from the S compartment and an outer (so negative) flow to the R compartment.

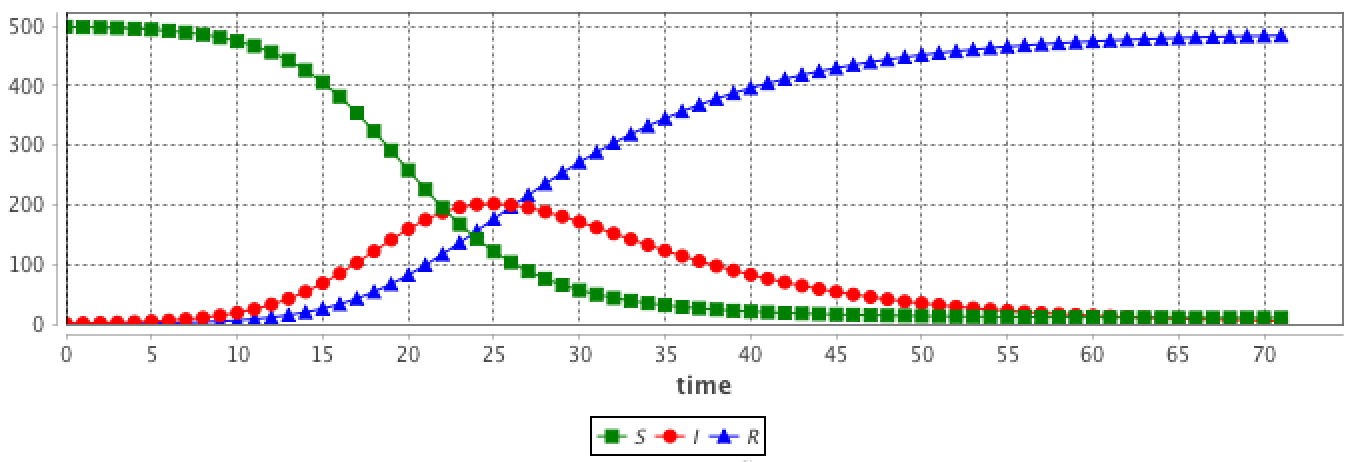

Integrating this system using the Runge-Kutta 4 method provides the evolution of S, I and R over time. The initial values are:

- S = 499

- I = 1

- R = 0

- beta = 0.4

- gamma = 0.1

- h = 0.1

Why and when can we use ODE in agent-based models?

These hypotheses are very strong and cannot be fulfilled in agent-based models.

But in some multi-scale models, some entities can be close. For example, if we want to implement a model describing the worldwide epidemic spread and the impact of air traffic on it, we cannot simulate the 7 billion people. But we can represent only cities with airports and airplanes as agents. In this case, cities are entities with a population of millions of inhabitants, that will not be spatially located. As we are only interested in the disease spread, we are only interested in the number of infected people in the cities (and susceptibles and recovered too). As a consequence, it appears particularly relevant to describe the evolution of the disease in the city using an ODE system.

In addition, these models have the advantage to not be sensible to population size in the integration process. Dozens of billions of people do not bring a computation time increase, contrarily to agent-based models.

Use of ODE in a GAML model

A stereotypical use of ODE in a GAMA agent-based model is to describe species where some agents attribute evolution is described using an ODE system.

As a consequence, the GAML language has been increased by two main concepts (as two statements):

- equations can be written with the

equationstatement. Anequationblock is composed of a set ofdiffstatement describing the evolution of species attributes. - an equation can be numerically integrated using the

solvestatement

equation

Defining an ODE system

Defining a new ODE system needs to define a new equation block in a species. As an example, the following eqSI system describes the evolution of a population with 2 compartments (S and I) and the flow from S to I compartments:

species userSI {

float t ;

float I ;

float S ;

int N ;

float beta<-0.4 ;

float h ;

equation eqSI {

diff(S,t) = -beta * S * I / N ;

diff(I,t) = beta * S * I / N ;

}

}

This equation has to be defined in a species with t, S and I attributes. beta (and other similar parameters) can be defined either in the specific species (if it is specific to each agent) or in the global if it is a constant.

Note: the t attribute will be automatically updated using the solve statement; it contains the time elapsed in the equation integration.

Using a built-in ODE system

In order to ease the use of very classical ODE system, some built-in systems have been implemented in GAMA. For example, the previous SI system can be written as follows. Three additional facets are used to define the system:

type: the identifier of the built-in system (here SI) (the list of all built-in systems are described below),vars: this facet is expecting a list of variables of the species, that will be matched with the variables of the system,params: this facet is expecting a list of variables of the species (of the global), that will be matched with the parameters of the system.

equation eqBuiltInSI type: SI vars: [S,I,t] params: [N,beta] ;

Split a system into several agents

An equation system can be split into several species and each part of the system are synchronized using the simultaneously facet of equation. The system split into several agents can be integrated using a single call to the solve statement. Notice that all the equation definition must have the same name.

For example, the SI system presented above can be defined in two different species S_agt (containing the equation defining the evolution of the S value) and I_agt (containing the equation defining the evolution of the I value). These two equations are linked using the simultaneously facet of the equation statement. This facet expects a set of agents. The integration is called only once in a simulation step, e.g. in the S_agt agent.

global {

int N <- 1000;

float hRK4 <- 0.01;

}

species S_agt {

float t ;

float Ssize ;

equation evol simultaneously: [ I_agt ] {

diff(Ssize, t) = (- sum(I_agt accumulate [each.beta * each.Isize]) * self.Ssize / N);

}

reflex solving {solve evol method: #rk4 step_size: hRK4 ;}

}

species I_agt {

float t ;

float Isize ; // number of infected

float beta ;

equation evol simultaneously: [ S_agt ] {

diff(Isize, t) = (beta * first(S_agt).Ssize * Isize / N);

}

}

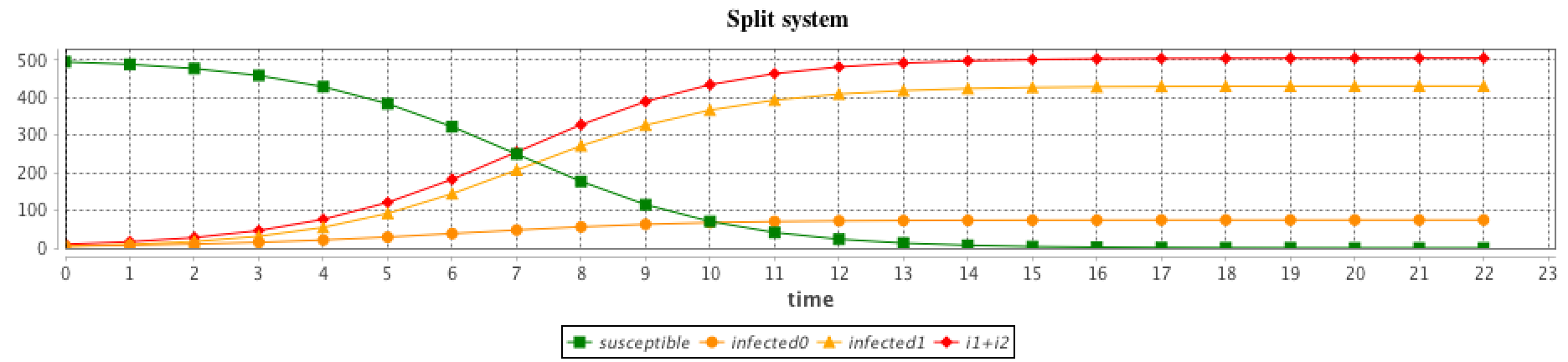

The interest is that the modeler can create several agents for each compartment, which different values. For example in the SI model, the modeler can choose to create 1 agent S_agt and 2 agents I_agt. The beta attribute will have different values in the two agents, in order to represent 2 different strains.

global {

int number_S <- 495 ; // The number of susceptible

int number_I <- 5 ; // The number of infected

int nb_I <- 2;

float gbeta <- 0.3 ; // The parameter Beta

int N <- number_S + nb_I * number_I ;

float hRK4 <- 0.1 ;

init {

create S_agt {

Ssize <- float(number_S) ;

}

create I_agt number: nb_I {

Isize <- float(number_I) ;

self.beta <- myself.gbeta + rnd(0.5) ;

}

}

}

The results are computed using the RK4 (Runge-Kutta 4) method with:

- number_S = 495

- number_I = 5

- nb_I = 2

- gbeta = 0.3

- hKR4 = 0.1

solve an equation

The solve statement has been added in order to integrate numerically the equation system. It should be executed into a reflex. At each simulation step, a step of the integration is executed, the length of the integration step is defined in the step_size facet. The solve statement will update the variables used in the equation system. The integration method (defined in method) can be chosen among the ones provided, e.g. Runge-Kutta 4 (which is very often a good choice of integration method in terms of accuracy).

reflex solving {

solve eqSI method: #rk4 step_size: h;

}

With a bigger integration step, the integration will be faster but less accurate.

More details

Details about the solve statement

The solve statement can have a huge set of facets (see (this page)[Statements#solve] for more details). The basic use of the solve statement requires only the equation identifier. By default, the integration method is Runge-Kutta 4 with an integration step of 1, which means that at each simulation step the equation integration is made over 1 unit of time (which is implicitly defined by the system parameter value).

solve eqSI ;

Integration method with the method facet

Several integration methods can be used in the method facet. Here are the 3 most common ones:

method: #rk4will use the Runge-Kutta 4 integration methodmethod: #dp853will use the Dorman-Prince 8(5,3) integration method. The advantage of this method compared to Runge-Kutta is that it has an evaluation of the error and can use it to adapt the integration step size.method: #Eulerwill use the Euler integration methode. This method is perhaps the simplest one but suffers from precision issues.

GAMA relies on the Apache Commons Math library to solve the equations; it thus provides access to the various solvers integrated into the library. The list of all the solver is detailed in this page, section 15.4 Available integrators. The GAML constants associated with each of them (to use in the method statement) are:

- Fixed Step Integrators

- Adaptive Stepsize Integrators

#HighamHall54for Higham and Hall#DormandPrince54for Dormand-Prince 5(4)#dp853for Dormand-Prince 8(5,3)#GraggBulirschStoerfor Gragg-Bulirsch-Stoer#AdamsBashforthfor Adams-Bashforth#AdamsMoultonfor Adams-Moulton

Integration steps

In order to improve the precision of the integration or its speed, the integration step can be set using the step_size facet. Its default value is 1, but classical use is to set it to 0.01.

step_size(float): integration step, use with most integrator methods (default value: 1)

This value is very important in some solvers, the Fixed Step Integrators, that keep the same integration step value all over the integration. One drawback is that the integration does not require the same precision all over its computation: a high precision is needed in part with a lot of variations, whereas in a quite stable part a low precision could be enough. The interest of the Adaptive Stepsize Integrators (e.g. #dp853) is that their integration step is not constant. Such integrators require thus more information, through the following mandatory facets:

min_step,max_step(float): these 2 values define the range of variation for the integration step. As an example, we can use:min_step:0.01 max_step:0.1.scalAbsoluteToleranceandscalRelativeTolerance(float): they defined the allowed absolute (resp. relative) error. As an example, we can use:scalAbsoluteTolerance:0.0001 scalRelativeTolerance:0.0001.

Synchronization between simulation and integration

The simulation and the integration are synchronized: if one simulation step represents 1 second, then one call of the solve statement will integrate over 1s in the ODE system. This means that the step attribute of the global has an impact on the integration. See below to observe this influence.

It is thus important to specify the unit of the parameters used in the ODE system (in particular relatively to time).

It is also important to notice that the integration step step_size will only control the precision of the integration. If step (of the global) is 1#s, then after 1 call of solve, 1#s has flowed in the equation system. If step_size is set to 1#s or to 0.01#s will not impact this fact. The only difference is that in the latter case, the solver made 100x more computations than in the former one (increasing the precision of the final result).

Additional facets

Here are additional facets that be added to the solve statement:

t0(float): the first bound of the integration interval (default value: cycle*step, the time at the beginning of the current cycle.)tf(float): the second bound of the integration interval. Can be smaller than t0 for a backward integration (default value: cycle*step, the time at the beginning of the current cycle.)

Intermediate results

In one simulation step, if the statement resolve is called one time, several integration steps will be done internally. If we want to get the intermediate computation results, we can use the notation: var[] that returns the list of intermediate values of the variable var involved in an equation. As an example, with a SIR equation:

species agent_with_SIR_dynamic {

int N <- 1500 ;

int iInit <- 1;

float t;

float S <- N - float(iInit);

float I <- float(iInit);

float R <- 0.0;

float alpha <- 0.2 min: 0.0 max: 1.0;

float beta <- 0.8 min: 0.0 max: 1.0;

float h <- 0.01;

equation SIR{

diff(S,t) = (- beta * S * I / N);

diff(I,t) = (beta * S * I / N) - (alpha * I);

diff(R,t) = (alpha * I);

}

reflex solving {

solve SIR method: #rk4 step_size: h ;

write S[];

write I[];

write R[];

write t[];

}

}

We can use S[], I[], R[] and t[] to access the list of intermediate variables of these 4 variables. As S[] is a list, if we want to access the first element, we need to write S[][0].

We can also note that the current value of a variable, i.e. S, equals to the last value of the list S[]: S = last(S[]).

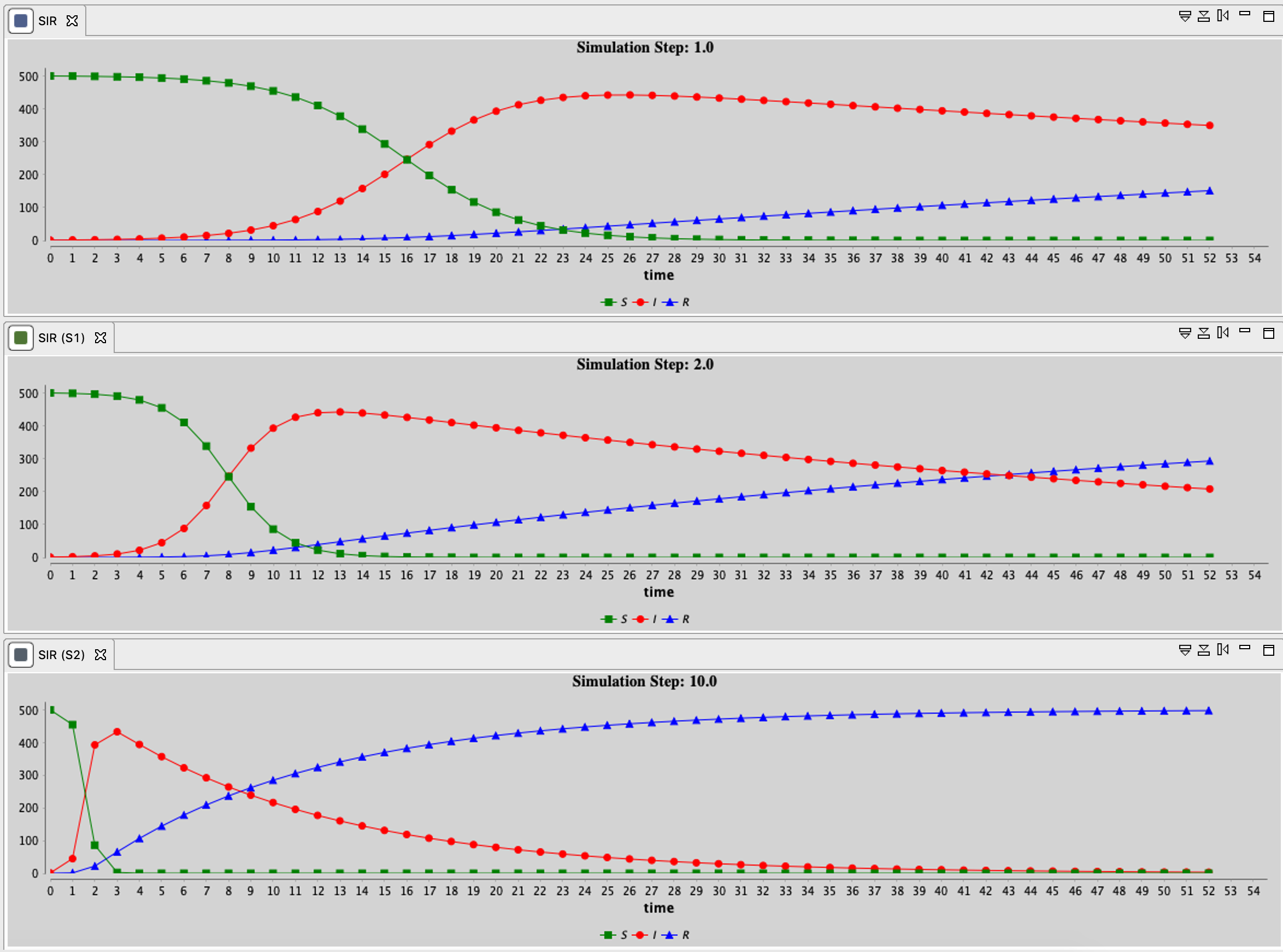

Example of the influence of the integration step

The step (of the global) and step_size (of solve) facets may have a huge influence on the results. step_size has an impact on the result accuracy. In addition, as mentioned previously, simulation and integration steps are synchronized: altering the step value, impact the integration.

The following image illustrates this impact, by calling (with 3 different values of step):

reflex solving {

solve eqSIR method: #rk4 step_size: 0.01 ;

}

List of built-in ODE systems

Several built-in equations have been defined.

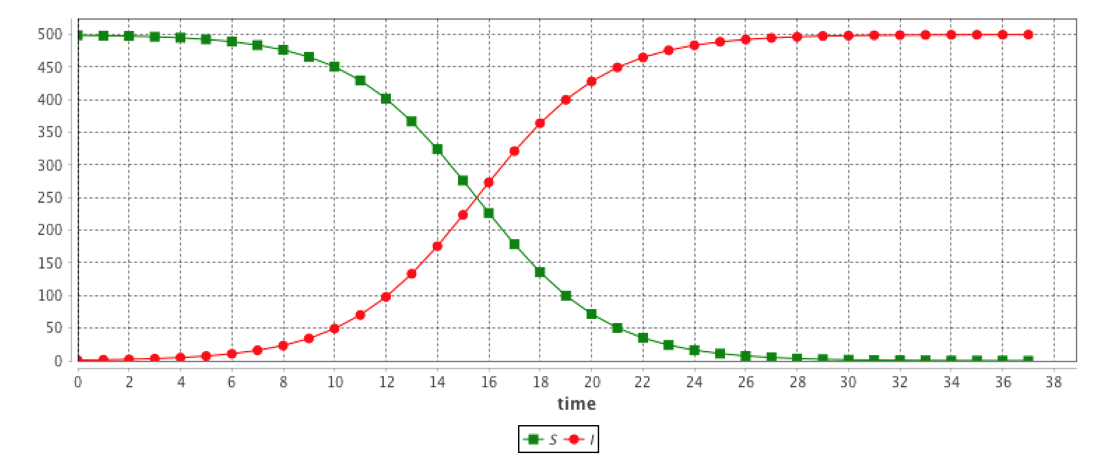

SI

The system:

equation eqBuiltInSI type: SI vars: [S,I,t] params: [N,beta];

is equivalent to:

equation eqSI {

diff(S,t) = -beta * S * I / N ;

diff(I,t) = beta * S * I / N ;

}

The results are provided using the Runge-Kutta 4 method using following initial values:

- S = 499

- I = 1

- beta = 0.4

- h = 0.1

SIS

The system:

equation eqSIS type: SIS vars: [S,I,t] params: [N,beta,gamma];

is equivalent to:

equation eqSIS {

diff(S,t) = -beta * S * I / N + gamma * I;

diff(I,t) = beta * S * I / N - gamma * I;

}

The results are provided using the Runge-Kutta 4 method using following initial values:

- S = 499

- I = 1

- beta = 0.4

- gamma = 0.1

- h = 0.1

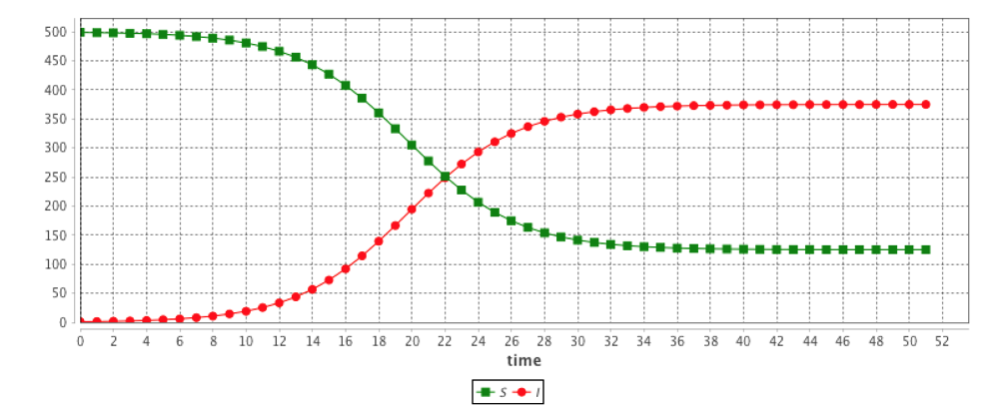

SIR

The system:

equation eqSIR type:SIR vars:[S,I,R,t] params:[N,beta,gamma] ;

is equivalent to:

equation eqSIR {

diff(S,t) = (- beta * S * I / N);

diff(I,t) = (beta * S * I / N) - (gamma * I);

diff(R,t) = (gamma * I);

}

The results are provided using the Runge-Kutta 4 method using following initial values:

- S = 499

- I = 1

- R = 0

- beta = 0.4

- gamma = 0.1

- h = 0.1

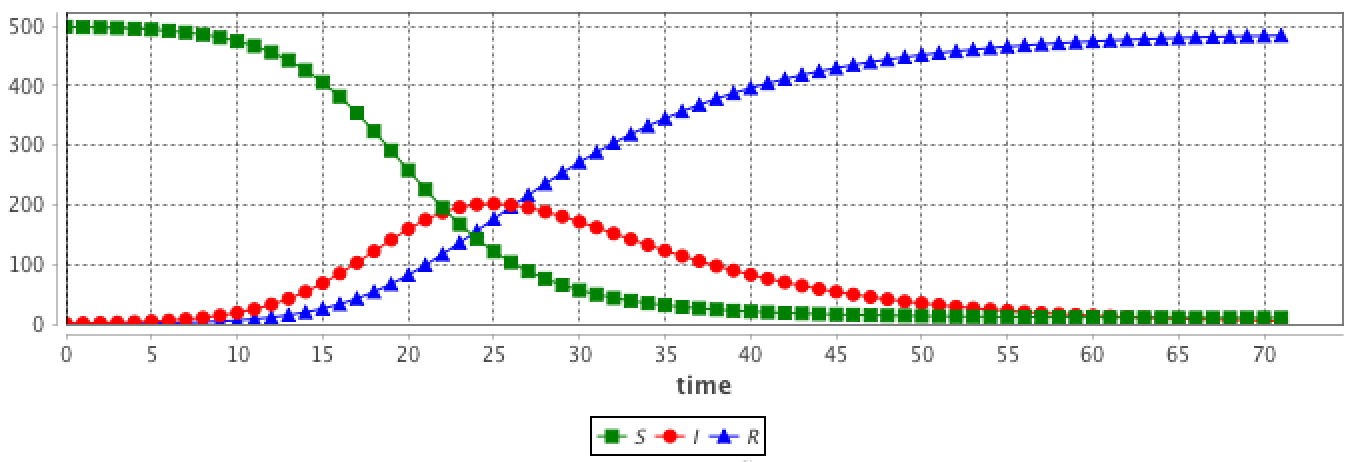

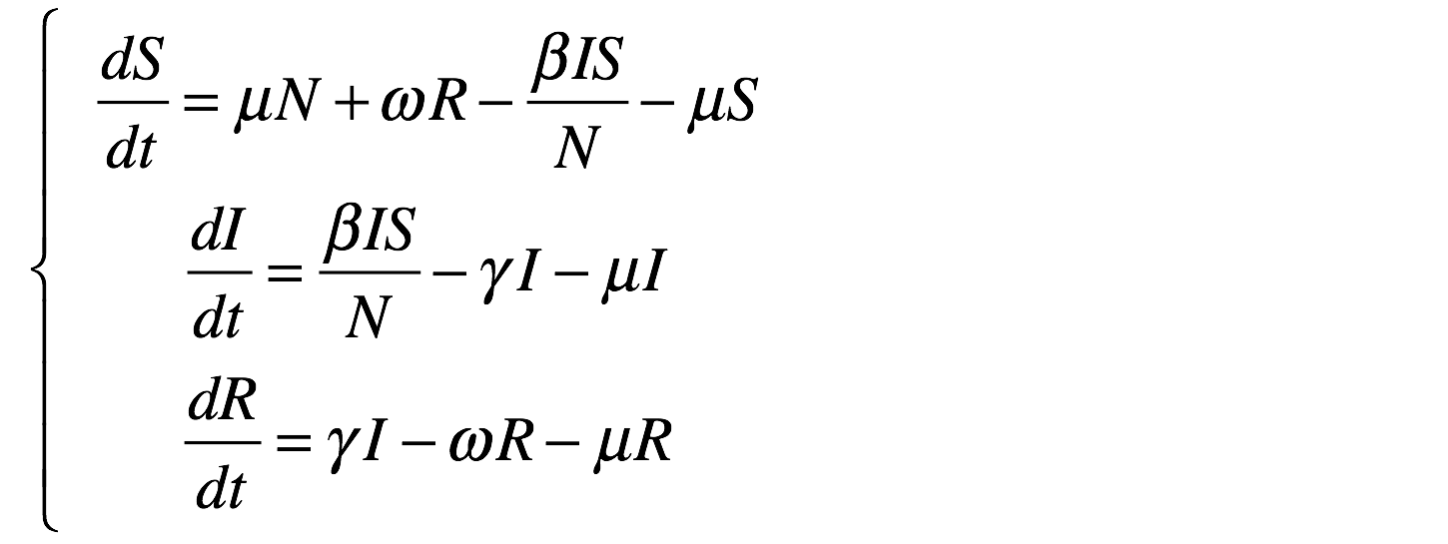

SIRS

The system:

equation eqSIRS type: SIRS vars: [S,I,R,t] params: [N,beta,gamma,omega,mu] ;

is equivalent to:

equation eqSIRS {

diff(S,t) = mu * N + omega * R + - beta * S * I / N - mu * S ;

diff(I,t) = beta * S * I / N - gamma * I - mu * I ;

diff(R,t) = gamma * I - omega * R - mu * R ;

}

The results are provided using the Runge-Kutta 4 method using following initial values:

- S = 499

- I = 1

- R = 0

- beta = 0.4

- gamma = 0.01

- omega = 0.05

- mu = 0.01

- h = 0.1

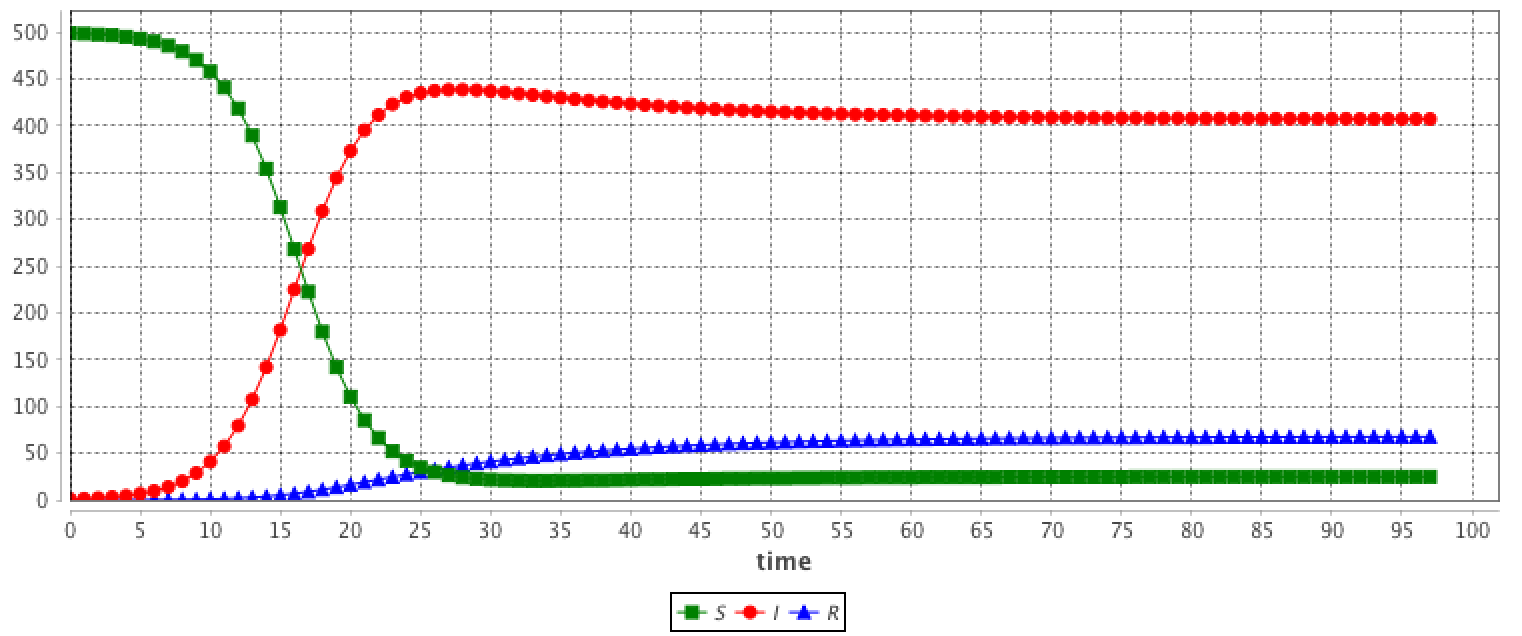

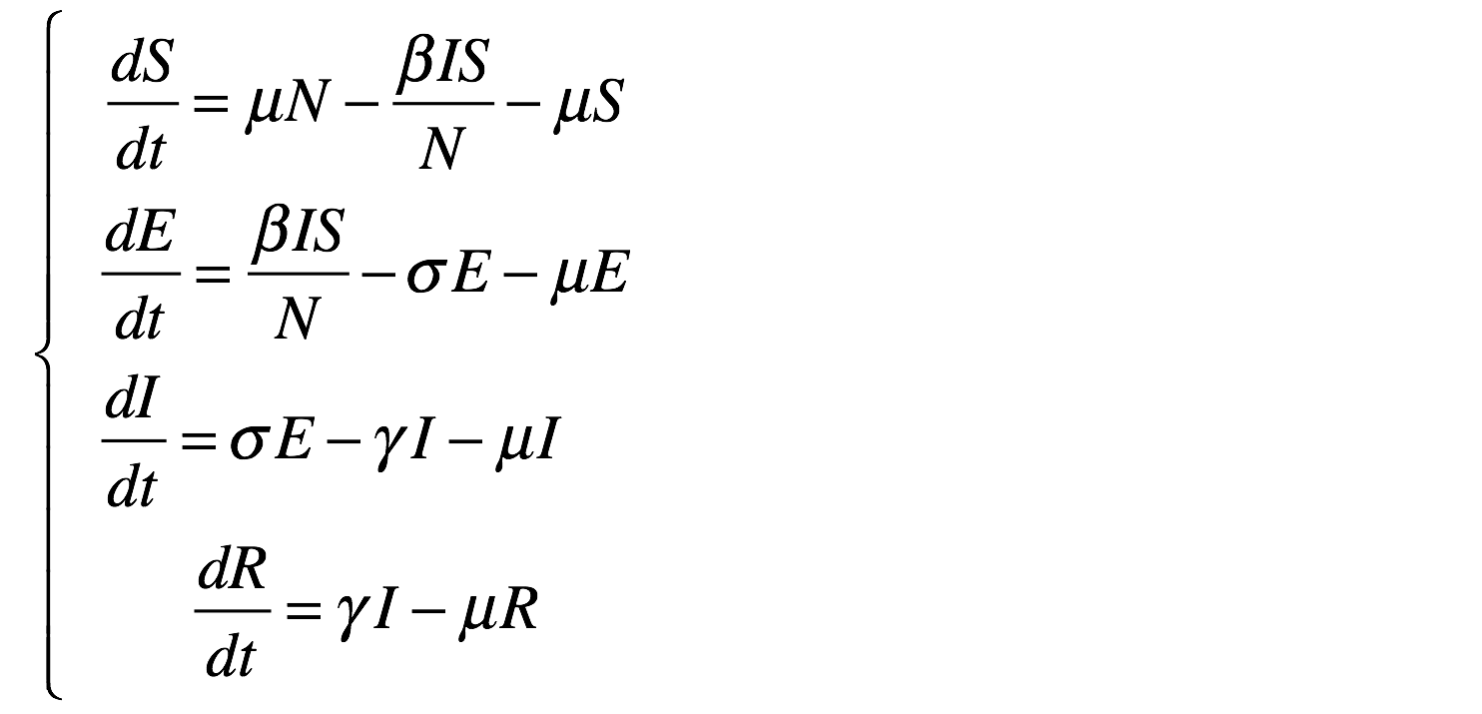

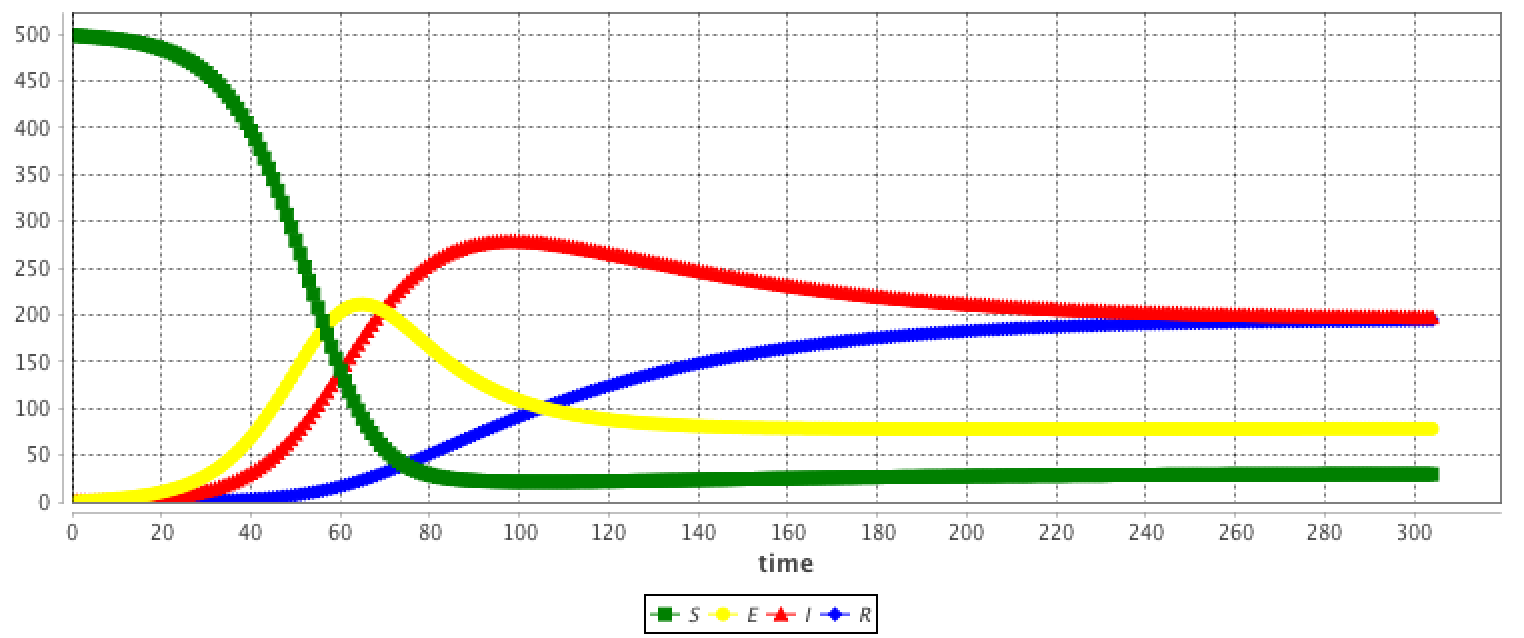

SEIR

The system:

equation eqSEIR type: SEIR vars: [S,E,I,R,t] params: [N,beta,gamma,sigma,mu] ;

is equivalent to:

equation eqSEIR {

diff(S,t) = mu * N - beta * S * I / N - mu * S ;

diff(E,t) = beta * S * I / N - mu * E - sigma * E ;

diff(I,t) = sigma * E - mu * I - gamma * I;

diff(R,t) = gamma * I - mu * R ;

}

The results are provided using the Runge-Kutta 4 method using following initial values:

- S = 499

- E = 0

- I = 1

- R = 0

- beta = 0.4

- gamma = 0.01

- sigma = 0.05

- mu = 0.01

- h = 0.1

LV

The system:

equation eqLV type: LV vars: [x,y,t] params: [alpha,beta,delta,gamma] ;

is equivalent to:

equation eqLV {

diff(x,t) = x * (alpha - beta * y);

diff(y,t) = - y * (delta - gamma * x);

}

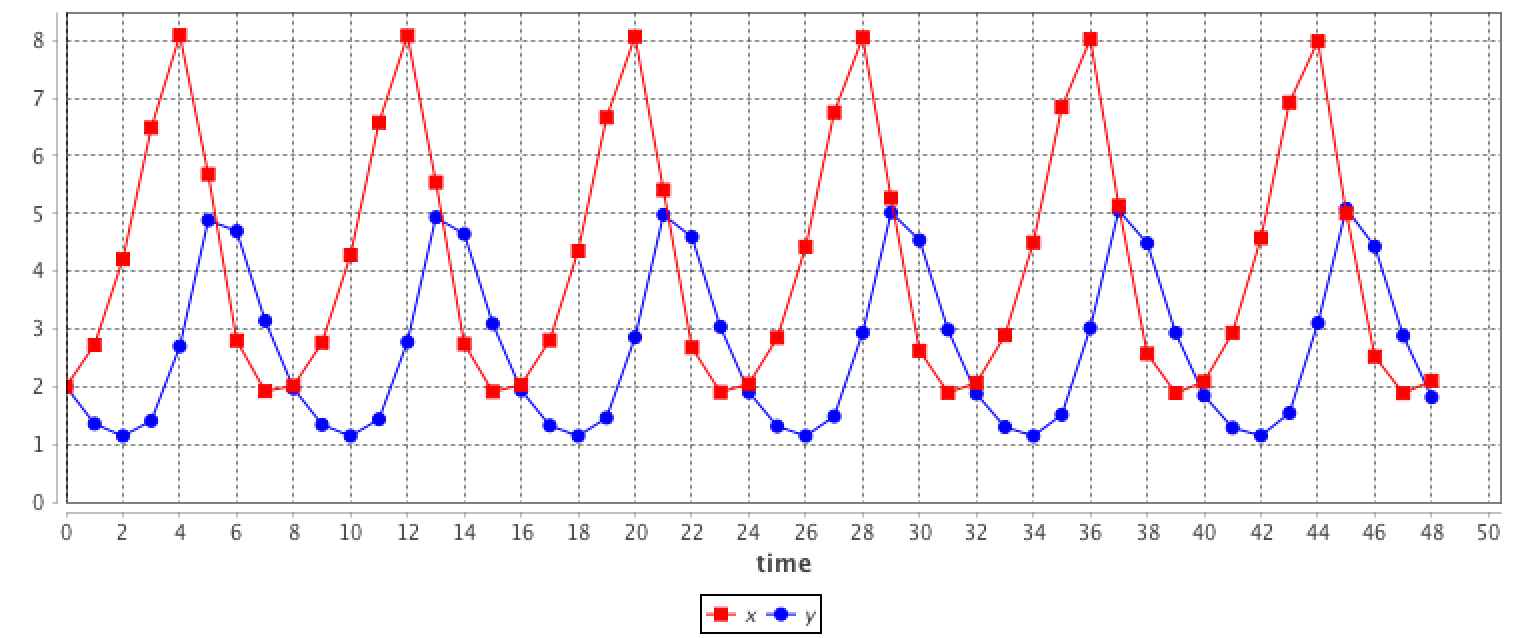

The results are provided using the Runge-Kutta 4 method using following initial values:

- x = 2

- y = 2

- alpha = 0.8

- beta = 0.3

- gamma = 0.2

- delta = 0.85

- h = 0.1